THE GARRET

It’s where everything happens. It’s my sanctum, my mirror, my protector, my arms and legs, my palimpsest, my nurturer. The four walls record the accounts (paid and owed) of my life and measure their growth-lines not unlike that of a child growing up. Each year  and place designate a noteworthy experience, some of which still elicit new responses. All things still significant earn another line and number. The garret is a record (and story) of my life.

and place designate a noteworthy experience, some of which still elicit new responses. All things still significant earn another line and number. The garret is a record (and story) of my life.

I forget its importance until I get home each day. Then magically it becomes my heart and lungs, filling up with blood and air ready to exhale the day’s events. And almost instinctively I disgorge all that the day had forced upon me, the day’s final stamp. Most often I simply “unload” as a gesture to that space of gratitude to have arrived. Other days I lean over and scream with anger, frustration, and regret, and my walls seem to understand. On still others I surprise myself with nothing to report. On those days there is no “writing on the wall” because all went reasonably well. My inner world aligned peacefully with the outer and I managed  to maintain an air of amicability with everything. On those days I’m rather surprised at myself and then try to understand why there aren’t more of them. The garret then accommodates a space for self-examination and reflection.

to maintain an air of amicability with everything. On those days I’m rather surprised at myself and then try to understand why there aren’t more of them. The garret then accommodates a space for self-examination and reflection.

The garret has a rich history which, when applied to my home, transforms it into what it was for so many others. Originally meaning “watchtower” or “place of protection” (garite in Middle English and Old French), it stands to reason it would later refer to an attic or loft. “Garrison” is another derivation. Not surprisingly, the military connotation never meant to imply a place of comfort or leisure, and modern garrets have lived up to their reputation. Cold, drafty, no water or heat (cold water only when running), leaky roofs, small and cramped, often shared by more than one person – they were the poor man’s flop. Or the student’s. Which both together common translated to “the artist.” What furniture existed usually belonged to persons unknown, clothes found and reclaimed were left by previous renters, and the rent itself was paid usually to third-parties who knew the landlord, who knew the owner – precursor to the “slumlord.”

The wonderful thing about having a garret is that it invites that part of ourselves which can’t surface anywhere else. It summons the creative voices and feelings deeply hidden and promises no interruptions or moral condemnations which blindside us otherwise, before even having a chance to make a sound. It is an empty canvass telling me it’s ready to be painted over. And nothing is permanent. The oils disappear unless I wish to record them (on the wall). For most artists historically the garret was so uncomfortable that it was barely habitable, and they would go elsewhere (cafes mostly) to do their work. I’m fortunate in that my garret furnishes me with the comforts of “home” – such as it is. And it invites me to stay nearly full-time. The only anxiety it fosters is the unavoidable problem of monotony, then boredom. As much as it tries, it cannot duplicate the ambient sounds of the cafe which keeps me focused and alert. I get cabin fever and simply must leave.

In the 1820s Balzac had cabin fever. When he felt trapped with nowhere to go, he would “imagine” his garret to be something totally different from what it was in design and furnishings. Given little more than a table, bed, and a chair by the landlord, he dressed the room up in words – imagining a chair “over there,” a sofa “over here,” and expensive painting and drapes in adjoining rooms that didn’t exist. He would leave notes in places saying “ottoman & chair” or “fireplace.” On one wall he inscribed, “Rosewood paneling with commode.” On the opposite wall, “Gobelin tapestry with Venetian mirror.” And over the fireplace, “Picture by Raphael.” (After becoming rich and famous he filled his own apartments with “reminders” – Venetian mirrors, rare porcelain, original paintings). – This was the best he and others could do during the lean years. When without, be creative … use the “watchtower” of escape to escape again.

The marooned feeling is a familiar one, but in my case it encompasses a wider radius. It’s about being in the wrong city, in the wrong culture, in the wrong country. Mentally I paste notes on places that don’t exist, or, if they do exist, I imagine my garret being somewhere else. In the city where I currently reside, I have but one cafe to offer the kind of atmosphere needed to keep me creatively focused and “out of the house.” Not to sound like a postcard, but it has wonderful espresso, great food, an impressive used bookstore (very important), a friendly staff, and (depending on the time of day) even nice music – all conducive to the requirements of creative writing. If it weren’t for Poor Richards, if for some reason it closed, it would literally be the final straw which led me to sell and find another garret in another city. Such as it is, thankfully, Poor Richards has become a landmark business. Too many people depend on it.

Poor Richards and the very small inner-city enclave surrounding it – a marginally “leftist” neighborhood – reminds me of an inner city arrondissment encased inside much larger arrondissments which are (by contrast) anything but artistic. It’s like an oasis surrounded by a rigidly conservative and religious population, three military bases, and a kind of mass-consciousness that wouldn’t know an espresso from a Dr. Pepper – as someone rudely announced, “caffeine is caffeine, so shut up!”

Predictably, the ambient theme of this city is one of “toughness” – in every way imaginable. Reflection, silence, ambivalence, smallness, femininity, softness, understanding, forgiveness, and so forth are all forms of “weakness.” Male machismo is paraded daily either in the form of large trucks and big engines, deafeningly loud motorcycles, killer dogs, guns, prison “tatts,” and of course the ubiquitous military uniform. Voters are “manly” on everything, and while the city’s jails overflow with “tough people,” the city council doesn’t know what to do with them all. It seems unable to connect the dots between the attitude of intolerance and the repercussions of intolerance. Alan Watts called it the “law of reversed effort.”

Hence, the absolutely essential garret “of the mind” within an almost intolerable environment, without which surviving here would be impossible. In the few years I’ve lived here (don’t ask how I landed here in the first place) I’ve practically worn a path between garret and café. Two paths actually, both about equidistant. Walking is the preferred means of travel, as city driving is an additional nightmare. Arriving either home or at the café brings as sense of welcomed relief, but the commute elicits the feelings I have on living here.

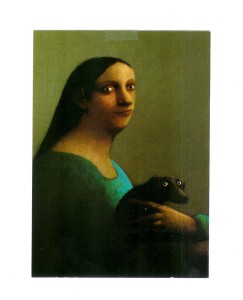

If body-language could speak, if I could make visible how it feels and what I possibly  actually look like to others – I would pick two images that come to mind. The first image is taken from an old Led Zeppelin album of a peasant farmer inured to the burdens of life. He carries it on his back. The second is a painting by the German artist Michael Sowa, entitled Herbert. The human is female, but it doesn’t matter. What does matter are the eyes – all four of them – vigilant, wary, guarded, reticent, observing, withheld, bonded together for survival. It captures the state of mind which is out of step, out of place, with their surroundings. The

actually look like to others – I would pick two images that come to mind. The first image is taken from an old Led Zeppelin album of a peasant farmer inured to the burdens of life. He carries it on his back. The second is a painting by the German artist Michael Sowa, entitled Herbert. The human is female, but it doesn’t matter. What does matter are the eyes – all four of them – vigilant, wary, guarded, reticent, observing, withheld, bonded together for survival. It captures the state of mind which is out of step, out of place, with their surroundings. The

look is one of discipline and fear behind cautious forbearance.

Not a good diagnosis if indeed pictures tell a thousand words. Outwardly, I have no idea what I look like or how I carry myself. Perhaps I fool everyone with a lighter countenance, but it doesn’t matter. It’s not something I consciously control anyway. I can’t speak for anyone else, but I just have an intuitive (gut) feeling that the facade I carry may be a familiar one to many others, and we just don’t let on. It’s ironic that so many share the same burdens and fears and still choose not to share that revelation. We’re all afraid of each other in this city. But we smile anyway.

Not all cities are the same. Hence, all garrets are not the same. Some cities fit the experience described by Henry Miller (near the Sacre Coeur basilica in Paris) – streets like “jagged knife wounds,” bars and cabarets running like “incandescent lace and froth of the electrical night,” a “night of the boulevards” looking like a “fretwork of open tombs,” the “soft Paris night … stand[ing] out in all its stinking loveliness.” Hence the visage of Herbert. But others inspire a much lighter impression. What irony it is that the urban environment can invoke such divergent reactions. The garret is stark and barren in most cities, but the adventures inside one’s four walls (recorded line-by-line) detail adventures of unexpected self-examination and learning.

So it is with confidence that I can say my residence here is temporary. How temporary is still an unknown. But if I can somehow make it another 60 miles north of here – to Colorado’s Big Apple, Gotham City of the Rockies, a place I know well and made my domicile for ten years, it just feels as if my “profile” would change dramatically. Denver is twice the size of Colorado Springs, filled with twice the crime, and so forth; but again – another irony, another “law of reversed effort.” Who can explain it? The only problem right now – affordability. We’ll see.

Part of the irony I look forward to in Denver is that in spite of so many people living in such close proximity, it is a much more liberal place, and the collective sense of tolerance, understanding, literacy (all the opposite adjectives which float about in Colorado Springs) all apply there. No killer dogs – (small, friendly dogs on leashes), far fewer military uniforms, fewer guns per capita neighborhood, a “roll-call” of cafes, bistros, and (used) bookstores, smaller vehicles (smaller engines) to fit congested roads and parking spaces, and so on.

Hence, the Denver garret, in my mind, being different as well. One generally gets less space for his dollar, and he can expect his surroundings to be compromised in more “challenging” ways. But it’s the “feeling” here that matters most of all. It’s about unburdening my back with so much debris, and relaxing the eyes. And, fitting right in with Herbert, it would be just as much for my own lapdog (Chihuahua) as it is more moi. Denver is the last “expatriation” from an old world mentality I will probably ever make – the whole of 60 miles. But who knows? It might as well be a thousand.

Despite the reduced size and a probable juxtaposition to various oddities (people and things), the Denver garret would actually contain a lower intensity of focused energy than what I currently occupy. It would be more relaxed, “casual,” and open-ended in a sense, even with less square footage. This is because the creativity needed would be disseminated more outside the garret. There’s the feeling of being safely included, embraced, if not by individuals then by places they patronize. It would reset the burden placed on the garret. It would no longer carry the entire load of daily sustenance. A new series of lines on the wall would begin to show. A new child would appear, showing rapid growth.

What are four walls anyway? They are what they contain. And in this day and age, with  so much alienation and estrangement in an environment which almost censors privacy anymore, the hearth becomes a whole new thing. It suddenly takes on a critical significance mentally, physically, and therapeutically. Without one, we are “exposed” in more ways than we can fathom and can usually handle, as demonstrated daily by the homeless. “There but for the grace of god ….” And in that sense, the hearth/garret is, like Balzac’s later apartments, a “reminder” of life without it. One is grateful for four walls and a tiled roof that doesn’t leak.

so much alienation and estrangement in an environment which almost censors privacy anymore, the hearth becomes a whole new thing. It suddenly takes on a critical significance mentally, physically, and therapeutically. Without one, we are “exposed” in more ways than we can fathom and can usually handle, as demonstrated daily by the homeless. “There but for the grace of god ….” And in that sense, the hearth/garret is, like Balzac’s later apartments, a “reminder” of life without it. One is grateful for four walls and a tiled roof that doesn’t leak.

© 2019 Richard Hiatt

for now. The twists and turns of this ruelle just go deeper and deeper and deeper. – Maybe I’ll see you at the other end. Or perhaps in a small cafe somewhere.

for now. The twists and turns of this ruelle just go deeper and deeper and deeper. – Maybe I’ll see you at the other end. Or perhaps in a small cafe somewhere. visages of Melpomene (muse of tragedy) and Thalia (muse of comedy) worshiping Dionysus.

visages of Melpomene (muse of tragedy) and Thalia (muse of comedy) worshiping Dionysus.