ANOTHER DIMENSION OF SIGHT AND SOUND

I’m feeling more and more like an unwelcome stranger in this world. Or should I say I’m the one inhospitable to it? It just feels wrong, out of sync, and toxic. I just got an e-mail this morning saying that two-thirds of the planet’s existing wildlife will be extinct by 2020. Ecologists are also saying we have “twelve years” left to save ourselves (and our children) from unsustainable conditions? How can anyone continue to believe in the pacifying notion of ”human ingenuity” to bale us out of a global cataclysm?

That aside, how does anyone even know what’s true anymore, who’s being honest, and if they even know when they’re being dishonest half the time? The situation itself seems insurmountable. Nature does survive, but just barely, and it’s a marvel of marvels that, as it hangs by a thread, it still hosts the human family and all its schemes and forgeries.

Nothing is not touched by human hands anymore. We’ve finally gotten what we wanted – total dominion over everything, from surveillance cameras to air-borne metals reaching the remotest mountain lakes, the (not so) frozen tundra, and nature’s food-chains. To put it in the simplest and most honest vernacular that I know, nothing is not fucked up anymore. It’s “anything but” a brave new world. It’s one of cowardice, denial, betrayal, and planned (legal) evasions all in the name of power and profit. The money-god rules absolutely. It’s no wonder that the Twin Towers were (still are) the most conspicuous monuments to man, not just in America but the world. They symbolize all that is most coveted and most hated at the same time.

Not to belabor this streak of “in your face” misanthropy, at least it offers an explanation for diving into my thoughts and fantasies which are becoming an almost permanent sanctum. I can’t get out of that orbit which has but one function, to find meaning, intelligence, and inspiration. I can’t escape it, but nor do I want to. There’s nothing else. Call it nostomania – a desire to go home.

When I speak of “night,” it is by no means circadian. The mind is a perpetual nocturne. But again, that’s okay. It’s instructive, and instruction is therapeutic, Tonight (which is this morning) I’m descending into another time-warp – a portal in the fabric of time. Without being able to explain it, I seem to be a “datum” in the validation of “loop quantum gravitation,” “wormhole theory,” “space-time bends,” “string theory,” and/or parallel universes. Whatever it’s called, I’m suddenly in a different time and place. It even smells of a different time/place on earth – if only for the absence of toxic fumes in the urban air.

The title of this entry belongs to Rod Serling. And it’s fitting because tonight is a Twilight Zone – “a fifth dimension… the middle ground between light and shadow, between science and superstition, [lying] between the pit of man’s fears and the summit of his knowledge. This is the dimension of imagination.” – It also escapes “what man has deeded to himself” – a loaded phrase too monstrous to contemplate.

I’m flaneuring tonight. I turn a corner and step through that rip in space-time. It’s still the 21st century, but it might as well not be. I stumble into places which are ancient but which fascinate me. The first is the Cafe Tingis, in Tangier, Morocco. Not so long ago Tangier was the hangout for artists and writers like Matisse, Genet, Burroughs, Camus, and Bowles. It was Paul Bowles who romanced it the most – and still does. To Burroughs it smells of “hashish, seared meat, and sewage,” and the native residents themselves “have a high tolerance for mad people.” It’s the place to “smoke hashish and pet my pet gazelle.” Life as a story of trade-offs and melodrama finds no better home than here in Tangier.

But these survivor-expats from the war are latecomers. The city has been resurrected and reinvented ever since the Phoenicians, then the Romans, the Portuguese, and even the English. As a city of “people with pasts craving somewhere else,” the expats are only a passing busload of tourists. The Beat Generation is only here for fifteen years. Today (whenever that is), it’s a port city at the intersection of the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. Residents live from the sea – old nets and boats trained on harvests and customs that stretch before time.

Just inland from the Port of Tangier is the Medina, which means “fortress.” In the northern corner of the Medina is the Kasbah, in the south the Gran Soco, and in the middle the Petit Soco. The Petit Soco is the epicenter of everything – center of the universe. Burroughs calls it “the last stop,” the “switchboard.” It’s here where everyone comes to the Cafe Tingis. – Turkish coffee, espresso, and Turkish tobacco are indulged in wooden chairs older than one’s grandparents. It’s the template for Hollywood envy. It defies categories and (stereo-) types.

If the smells of figs, raisins, nuts, olives, strong cheese, garlic bread, olive oil, and fish does not offend, it then spins you into its aura and fills your pours with salt air. One then fills himself with the incense of tobacco and coffee beans for dessert. One smokes kif and eats majoun (cannibus jam) – what alcoholics still call a “social menace.” To Western noses, one either “stinks” horribly or disappears in the redolent aromatics of a driftwood and cobbled culture.

Writers past and present speak to me personally. Paul Bowles says, “I’ve always wanted to get as far away as possible from the place that I was born, both geographically and spiritually – to leave it behind.” A writer/journalist from our 21st century, Jonathan Dawson, says “Some people need to leave their home to find their home. I’m one of those people.” Dawson has lived here for twenty years. These are kindred souls with whom a deep connection finds it linkage again once we’re underground together.

The second place I pass is Arabian. It seems inevitable as I follow the redolent traces of tobacco and coffee. I’m on Hamra Street in Beirut – chic but ancient. The “rich & shameless” came here for years, to “the Paris of the Middle East.” One wouldn’t know it today, but it was its own Left Bank and Boulevard Saint-Germain. The late 20th century of course took care of all that – simply couldn’t tolerate “meccas” not having to do with war and death.

Still, amid the rubble and dust survives the “Hidden” Cortado Espresso Bar in heart of Beirut. It’s part of an entrepot of cultures – French, English, Arab – experienced most dramatically in its teas. This epicenter presents itself as something ultra-modern and “hip” while simultaneously wearing the scars of the Ottoman Empire, the Armenian Genocide of the First World War, and the present-day Social Nationalist Party (which could just as easily call itself the National Socialist Party). This is the “party of god” du jour waving swastikas, suicide bombs, and claiming dominion over everything.

But a more resilient Beirut survives here. Martyr’s Square, using the full irony of that term, presents its citizens in western clothes (no hijabs and keffiyehs), eclectic music, and an almost militant disdain for any signs of hysterical zealotry or martyrdom. People are young, educated, and very “western” in their Levi’s and political opinions. Like the Petit Soco in Tangier, Beirut is “the template and cockpit of the region,” says prime minister Saad Hariri. “Anyone wanting to deliver a message in the Middle East sends it first to Beirut.” There’s the old city and the new one – two millstones grinding away as a dress rehearsal for an uncertain future. There are always the degenerate thugs, but then also the protesters of all forms of thuggery. The streets are by no means “one-way” in this city – a fitting augury for this region.

I pass the Old Arabesque Cafe and smell patrons smoking shisha and swilling Lebanese coffee. Old timers are playing chess and backgammon on weathered outdoor tables. I pass the Al Naser Cafe and then the Cafe Saliba where patrons are all thickly mustached and “old” — members of a brotherhood going back before time. They appear somewhat agitated tonight. Evidently the old cafes are closing one-by-one and turning into clothes and trinket shops dictated by western values. It’s like robbing a man of his home, a table, a chair, and a partner at cards that have been his for 50 years. He gets up and shuffles over to the next cafe which has never been his (terra incognita), but he’s forced to invade another man’s space just to find sanctuary – only to be shuffled to a third, and then a fourth cafe. A tragic and sad resignation fills wrinkled eyes filled with stories we can only imagine. It’s a local diaspora no one talks about.

I move on. This region is riddled with too much violence and politics, despite its oases of enlightened intelligence. As the itinerant Mr. Bowles said frequently, “So, I’m off tomorrow. I can’t stand this rain any longer.” So I change direction entirely and face another time portal. I step through and suddenly I’m no longer anywhere near the Middle East. I’m back in Italy – another land of breads, olive oil, garlic, pasta, and coffees. To the gastronome there’s no beginning of end to this land. The natives will tell you this is where cuisine really started. Not to argue the point, my attention turns to something entirely unrelated to food. I sense history instead. Standing before me is a metaphor, the perfect symbol of the kinds of ruin inflicted upon nature and native peoples not unlike those in their Beirut cafes. This is the Piazza des Miracles – “center of miracles” – aka, Pisa, Italy. It’s also a city planted in a lagoon.

The symbol in question is no mystery. The famous tower was built over a two-century period ending in 1372 AD. (same time period as Notre Dame, also taking just under two centuries). The village already has many towers, and they all lean. In fact, everything in Pisa leans, so “leaning” is a non-issue. The architects simply compensate by simply making columns longer on one side.

In 1173 the foundation is laid and it already begins to settle wrongly – but to the north, not the south as it does today. In 1178 construction stops and is abandoned for another hundred years. By the 13th century construction resumes, but now it leans to the south. By 1370 it’s completed. The fitting of a bell-tower is supposed to correct and stabilize the entire structure. It does not. In fact, it makes it worse. Hence they install more steps and larger bells on the one side. – This is becoming the lesson of the proverbial “digging one’s hole deeper,” only this time ascending upward… the hole that gets higher.

In 1540 Galileo drops his balls, so to speak, from the belfry and makes his calculations about gravity. And nothing more is said or done about the tower until the 19th century. By now the south base has sunk 10 feet into the ground. Part of the first floor is almost gone. So in 1838 an architect (Alexandro de la desca) tries to remedy the problem by digging around it. But he accidentally hits the aquifer and the entire town is flooded. The tower lunges yet another foot to the south. It’s “a miracle” that it doesn’t crash to the ground by now. In fact, in 1902 another tower nearby crashes, an 18,000 ton pile of dust and rubble.

In the 1930s they try injecting cement to stop the water from weakening the foundation – only to make it lean again another 3 inches. – Then the war begins. The village scatters and residents became refugees. There’s no time to fix it. Then in 1944 the Allies enter Pisa only to find that the Nazis had demolished all the bell towers, thinking they were observation posts. Inexplicably, this one tower is left untouched – another miracle.

By the 1980s it’s leaning “17 feet off the perpendicular.” In 1989 another 900-year old tower crashes to the ground in another village (and this one isn’t even leaning).

In 1990 the Italian government declares the tower off-limits to tourists indefinitely. It’s a sad day for all of Tuscany. But another effort is put forth by a committee of engineers to “seriously” save it. In 1992 a state-of-the-art monitoring system with censors is installed to detect further movement and cracks. But by 1995 it’s determined that there are simply “too many doctors on this patient” making the whole situation worse yet again.

Finally, in 1997 an idea dawns on “the experts” that could have come from a child: “remove” soil from the north side. This idea is actually proposed in 1962 but is ignored. – It reminds me of the story of the large truck which can’t fit through a tunnel due to its height. All the experts toil over engineering diagrams, theories and formulas. Then a 13-year-old girl in a passing car suggests that they simply let air out of the truck’s tires. They do, and the truck is on its way.

So, in 1999 and only $25 million later, the tower actually readjusts “one-half inch north.” Eureka! The strategy works. But then, again, they run out of money and the government is forced to stop restoration. And for the last 20 years, having done nothing more to it, the decision is made to “not” fix it anymore, in fact to keep it famously crooked – “for tourism.” To straighten it they say is the equivalent of “removing the smile from the Mona Lisa.” They rationalize their waste, embarrassing ineptitude, and torpor by “intelligently” turning lemons into lemonade. — Oh, how clever and politically expedient! We humans are the only animals that blush – and flatter – or need to.

The tower story is man’s legacy to himself, a monument to man’s stupidity, technology becoming “tech-no–logic” and progress becoming regress (and “congress” – bureaucracy). It’s the equivalent of intelligence being measured by nothing more than the quantity of information one has – not in what he does with it. The tower is a symbol and metaphor for all the futilities which have surfaced today in the name of progress. We toil on the wrong side of our towers, dig holes which just get deeper, and try to capture sunlight by drawing our shades down. As Alan Watts said, we attempt to capture the air by grabbing it; capture our breath by holding it (only to lose it), and accordingly, try to save our souls only to lose them.

I seem to be doing a full-circle around the Middle East and back to France again. But here I’ll stop. The warp and woof of time has no ending if I choose to indulge it. I need to come back to “this moment” (the morning) and carpe diem (or the noctis). – Interesting that Horace’s original injunction was carpe diem quam minimum credula postero – “pluck the day, trusting as little as possible in the next one.”

This may have sounded like a tourist’s travel-guide, but as Bowles himself asked: “What is a travel book anyway?” It’s not hotel information on where to go, what to wear, and what to eat, but a “story of what happens to one person in a particular place, and nothing more than that.”

All I can come away with after this excursion is that things change while never changing – plus ca change. The human tragi-comedy simply dons new clothing and does the same dance for every audience in every place (geography) and time (generation-to-generation). I suppose wisdom is all about knowing this and extricating oneself from it. The emphasis then quickly shifts to “meanings,” to the journey itself.

Somehow I think of the limerick This is It by Alan Watts intended to answer the question of purpose: “I am It, You are It, He is It, She is It, We are It, They are It, It is It, and That is That!” – The journey is the meaning. I am my own journey. I am “It.” Paraphrasing Bowles, the “story” is me.

The Bhutanese, a people I could have visited had I continued my trek farther East, insist that “this is all an illusion.” They say not to get caught in its web. It’s just a dream – something I intuitively know and say to myself like a mantra but sometimes forget. NONE OF THIS IS REAL. What a revelation that is, a confirmation of what the soul has been trying to say all along.

It’s amazing that we can have dreams about the dream we’re in. We escape from the ritual escaping done from our real work in “other dimensions of sight and sound.”

© 2019 Richard Hiatt

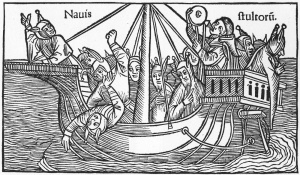

righteous climbed the spars and held up in the crow’s nest looking down on the unsaved.

righteous climbed the spars and held up in the crow’s nest looking down on the unsaved. important than substance and character. I chose that world because I was born into it and was successful at it. What do you expect?”

important than substance and character. I chose that world because I was born into it and was successful at it. What do you expect?”  Dorothy loves to spread malicious stories about, even as a member – all “hypocrites and show-offs.” Even an ordinary banquet meeting looks like a “road company for the Last Supper.”

Dorothy loves to spread malicious stories about, even as a member – all “hypocrites and show-offs.” Even an ordinary banquet meeting looks like a “road company for the Last Supper.”  sailed to Europe. As for women, I’m not the only one who was openly contentious and disdainful. For instance, you should have heard Zelda. She found them predictable and cowardly. In Scott’s novel she says that the only reason women collect men is to shake their boredom.

sailed to Europe. As for women, I’m not the only one who was openly contentious and disdainful. For instance, you should have heard Zelda. She found them predictable and cowardly. In Scott’s novel she says that the only reason women collect men is to shake their boredom.

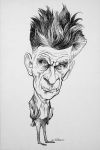

the absurd; and from the 1960s until his death when his themes become abstract and minimalist. From here on he’s clear that, where Joyce went in the direction of fulfillment, he was going in the direction of “impoverishment, in lack of knowledge … subtracting rather than adding.”

the absurd; and from the 1960s until his death when his themes become abstract and minimalist. From here on he’s clear that, where Joyce went in the direction of fulfillment, he was going in the direction of “impoverishment, in lack of knowledge … subtracting rather than adding.”